SPECIAL FEATURE

Mi'kmaw Fishing Economies

...through the lens of Cash Back

How can we tie current attacks on Mi'kmaw fishing rights to Canada's longstanding history of theft and fiscal discipline? What does the resurgence of Indigenous commercial fisheries by Mi'kmaqi look like today?

Every nation across each watershed has its own lifesprings, knowledge and history; each supports its own economies and livelihoods.

In Mi’kma’ki, the shores are laced with the tides of the Atlantic Ocean, St. Lawrence River, and its many tributaries and bays, where people have loved and lived for centuries. There was no need for grocery stores until European settlement collided with the rich fishing life of locals. Gradually, settlement crowded out Indigenous economies until even the sight of Mi’kmaw villages near white towns became too much to bear. A brutal relocation program followed that continues to bear bitter fruit today. But so too does the joy of Mi’kmaq ocean life continue to blossom, and the Indigenous laws of the land still govern its gifts.

Here we share a glimpse into Mi’kmaw fishing economies as they relate to the three parts of the fiscal relationship we outline in Cash Back.

PART ONE

The Theft of Mi'kmaw Economies (or, How Canada Got its Economy)

"Kill every buffalo you can! Every buffalo dead is an Indian gone.”

These are the words a colonel in the U.S. Calvary uttered in 1867. Called the “Indian’s commissary,” the buffalo stood in the way of a powerful movement west of cattle, ranchers, and railroad men intent on settling the prairies. The military drove the imperative to clear the plains and invited “sportsmen” to join the annihilation. Beaver trappers became bison killers, even “hunting by rail” from aboard the Union Pacific and the Kansas Pacific railroads, sharpshooting from roofs or windows.

In 2020, the carcasses of lobster piled outside a Mi’kmaw processing facility echoed the earlier carnage of the bison slaughter. Here was the livelihood of the Mi’kmaw fishers destroyed by another angry white mob. Instead of aiming to clear the land, now they tried to clear the waters.

Twenty-one years earlier, Mi’kmaw man Donald Marshall was acquitted of illegally fishing by proving he had Treaty rights under the Peace and Friendship Treaties, 1760–61. Mi’kmaw boats were attacked on the water by the Department of Fisheries and Oceans when they attempted to assert these rights, though.

A provisional program emerged for communal access to commercial fisheries for the Mi’kmaq, but a negotiated political settlement of their treaty rights never came.

So in the fall of 2020, the Sipekne’katik First Nation used their self-government powers to enact fishing rules and regulations under their Indigenous law — the L’nuwey Tplutaqan legal order of Netukulimk, defined by the Mi’kmaq as “use of the natural bounty provided by the Creator.” They were attacked again. White fishermen set fire to a van and mobbed Indigenous processing plants: First Nation “modest livelihood”— their “Indian commissary” — was once more interpreted as a threat.

LEARN MORE

- Yellowhead Brief | Colonizers Being Colonizers: Lobster Fishing & the Continued Oppression of L'nu'k in Mi'kma'ki by Melkita'n

- Yellowhead Brief | Peace, Friendship and Fishing in Mi'kma'ki by Hannah Martin

PART TWO

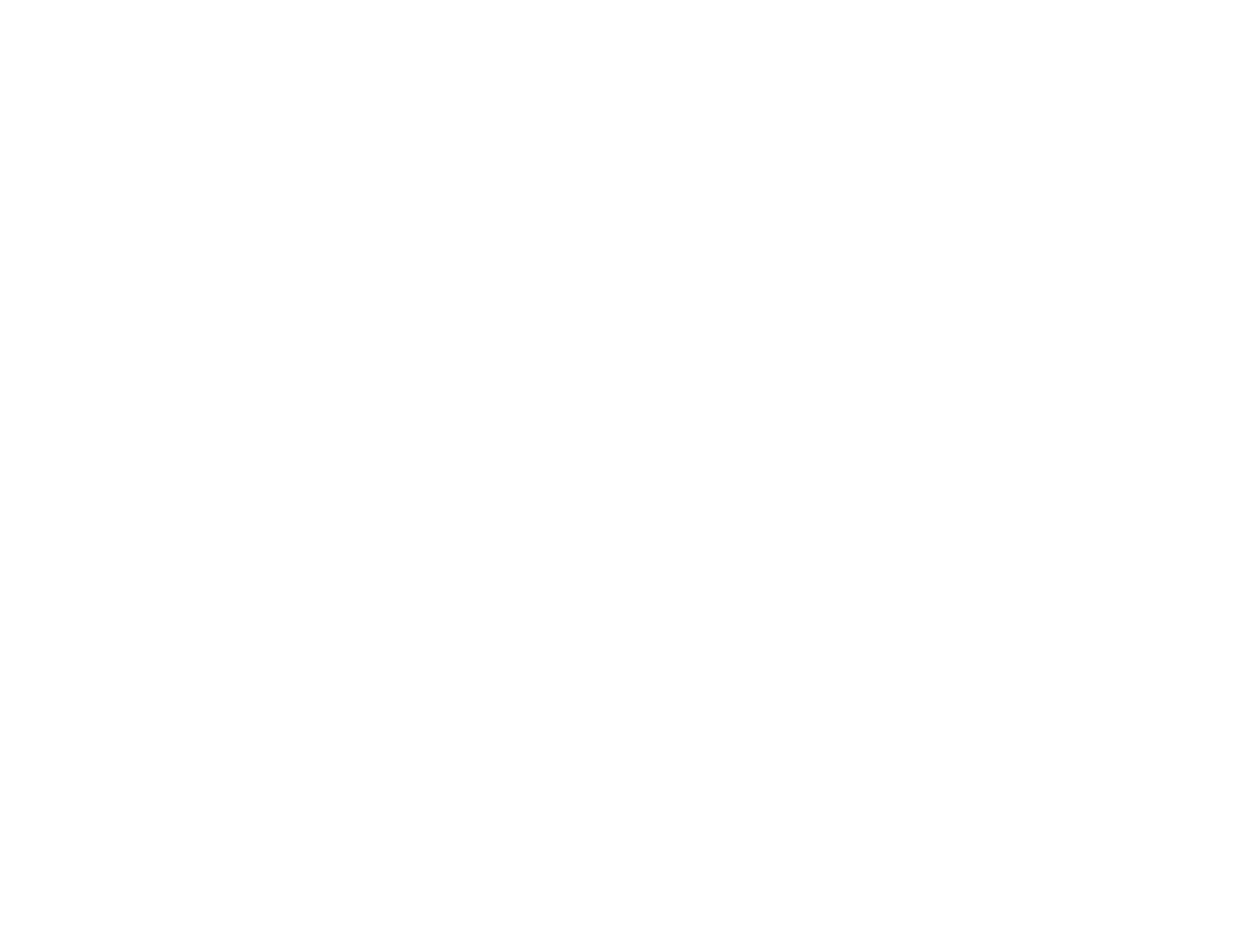

The Impacts of Centralization

(or, Fiscal Policy as Colonialism)

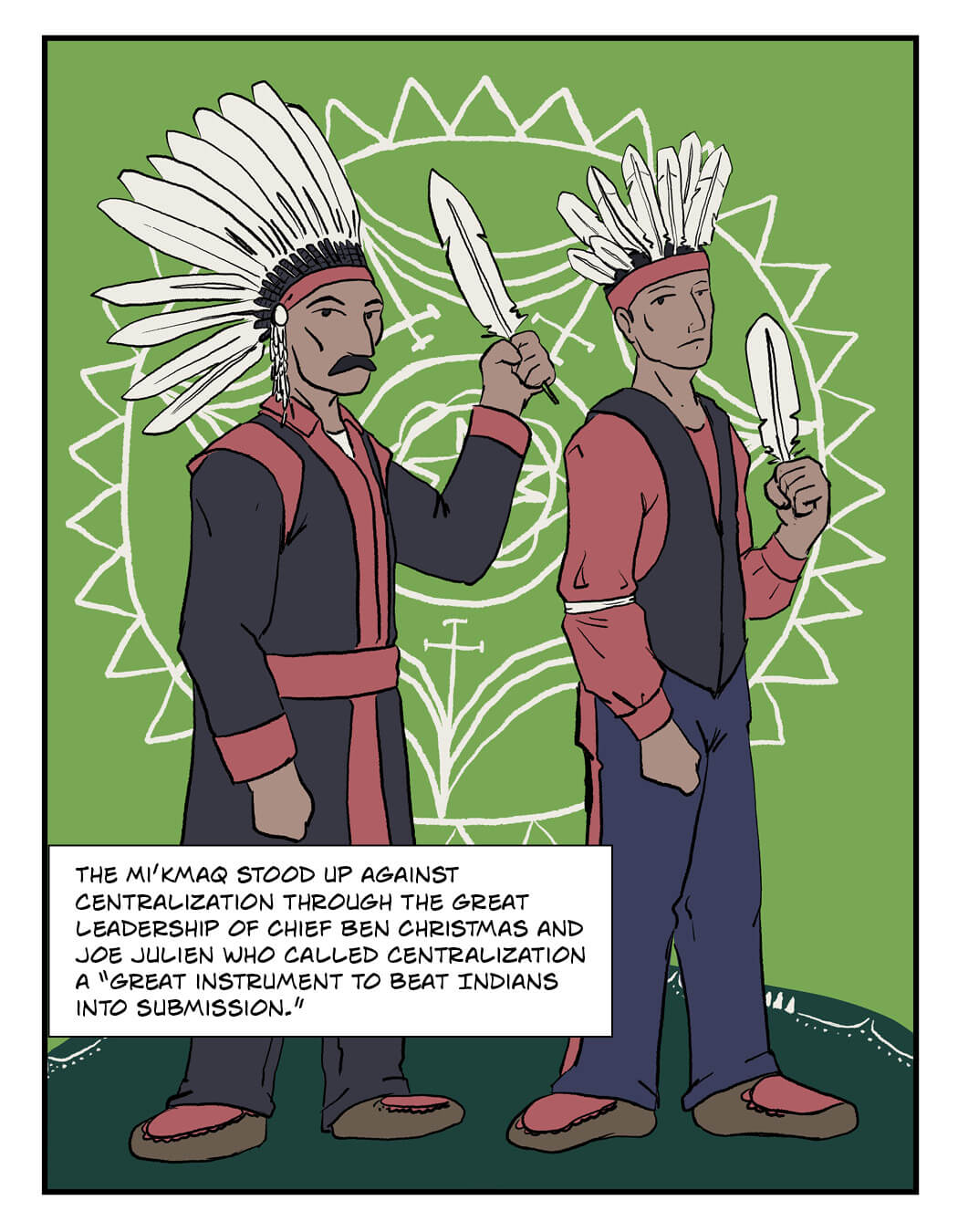

To save the bureaucracy a negligible amount of cash, and to hide First Nations away from cities, the province of Nova Scotia engaged in a massive relocation program involving thousands of Mi’kmaq citizens. The removal of people from their economic livelihoods led to cascading impacts: welfare dependency, shame, depression and addiction, family separation, and lingering inter-generational poverty. No reparations or apology were ever made. Here we share A Brief History of Centralization, illustrated by Brandon Mitchell (Mi’gmaq - Listuguj).

LEARN MORE

A Brief History of Centralization

(scroll through by clicking the green arrows)

Story by Shiri Pasternak

llustrations and script editing by Brandon Mitchell (Mi’gmaq - Listuguj),

Produced by Yumi Numata & Shiri Pasternak

PART THREE

Reclaiming Indigenous Economies in Mi'kmaqi (or getting that Cash Back)

As Fred Metallic, Director of Natural Resources, Listuguj Mi’gmaq Government, writes, commercial and sustenance economies are sometimes viewed as distinct concepts. As though you either fish to support your community, or you sell fish for profit. But both can be true at the same time. Yet the Department of Fisheries and Oceans treats Indigenous people, “as though we didn’t have proprietary knowledge or economic traditions prior to European arrival and their ideas of property and state sanctioned economic activity.” In other words, only subsistence fishing is recognized as a legitimate type of catch for First Nations.

“Nonetheless,” Metallic explains, “we’re trying to change the language around fishers, at a minimum with settlers we refer to our fisheries as hybrid fisheries or Gespe’gewa’gi fisheries, as a way to challenge either/or thinking on the ground/water. So much to impact within such a distinction.”

LEARN MORE

Press Release | Canada Recognizes Listuguj’s Laws and Authority in Fisheries Governance (April 18, 2021),Listuguj Mi'gmaq Government

"We firmly followed the mandate we received from Listugujewaq to assume control over our Fishery Governance. With this Agreement, we leave in the past a model where we were managing DFO’s regulations for a renewed relationship premised on recognition of our laws governing our rights in our territory..."

-SAQAMAW DARCY GRAY,

Listuguj Mi’gmaq Government Press Release

April 18, 2021